|

CHOISIR LE BON VILEBREQUIN ET COMPRENDRE SA TECHNIQUE

Ceci devrait vous aider à faire le bon choix

(Article de Stephen Kim...Photos de Johnny Hunkins)

(Traduction en cours de réalisation dés que j'ai un peu de temps...merci pour votre patience car ce n'est pas évident à faire...Sauf si vous lisez l'anglais techniques sans soucis...tant mieux pour vous !) (Traduction en cours de réalisation dés que j'ai un peu de temps...merci pour votre patience car ce n'est pas évident à faire...Sauf si vous lisez l'anglais techniques sans soucis...tant mieux pour vous !)

La course d'origine est réellement propre aux années 80 (nous parlons ici de la longueur de course mécanique caractérisée par le distance effectuée par l'ensemble bielles/pistons et vilebrequin dans le block moteur !); l'époque des gains minuscules et primitif obtenue à l'aide de vilebrequin retaillés, ajustés à la limite voir en dehors des côtes minimums fait belle et bien partie du passé depuis l'existence et la disponibilité à des prix relativement abordables, de kit stroker comprenant des pièces de différentes tailles et ces dernières les “cubic inch” n'ont jamais été aussi bon marché !

Parallèlement, la technologie des culasses à été dans l'obligation d'évoluer aussi face à la demande constante des longueur de courses obtenue avec cette disponibilité nouvelles de vilebrequin “stroker” , faisant augmenter la puissance des moteurs dans des proportions presque indécentes ! Comme notre passion est souvent centrée sur l'age d'or des mécaniques puissantes, il est important de savoir qu'aucune autre pièce du moteur, à l'exception des culasses, n'a autant fait avancer notre cause que ces vilebrequins modernes donc avant d'envisager quoi que ce soit sur votre auto pour gagner en puissance, si construisez un nouveau moteur vous irez probablement dans un premier temps vous renseigner chez votre marchand de pièces préféré afin de vous équiper d'un nouveau vilebrequin !

Le choix est vaste c'est le moins que l'on puisse dire mais tous les vilebrequins de sont pas égaux au niveau de leur conception ! Devez vous vous rabattre sur un vilo “cast steel” ou porter votre choix sur un vilo “forgé” ? Quelles sont les différences entres les aciers 5140, 4130, et 4340 ? avez vous réellement besoin de choisir l'acier “forgé” dans toutes les situations ?Est-ce que l'acier “Billet” mérite vraiment bien sa réputation ?? Comment faites vous la différence entre les produits “marketings” et les pièces de qualité ? Et plus important, quel est le bon vilebrequin pour votre application mécanique ?

Heureusement vous allez pouvoir trouver toutes ces informations manquante ici car nous avons contacté toutes les plus grosses société de fabrication de vilebrequin dans tout le pays afin de répondre définitivement à toutes les interrogations mentionnées dans les questions abordées précédemment, en abordant aussi le thème de la métallurgie ainsi que ses techniques variées de fabrication.

Ne vous inquiétez pas si vos connaissances sont plus centrées sur une marque plus qu'une autre puisque nous avons abordés plusieurs marques comme Chevrolet, Buicks, Olds, Ford et Pontiacs ...Lorsque certaines informations ne vont pas dans le sens de la perception commune du public et des passionné, les faits ne sont pas toujours facile à digérer...(assimiler)....Nous détenons les infos réelles et nous sommes sans le vrai mais pourrez vous le supporter ??? handle it?

Cast via Forged via Billet :

Les techniques de construction jouent un rôle essentiel dans la résistance ultime d'un vilebrequin; “casting” et “forging” sont les 2 méthodes de fabrication les plus employées et chacune d'entre elle ont des avantages et des inconvénients...Les vilo “Cast” cranks commencent leur vie sous forme de fer ou d'acier liquide et sont ensuite versés dans un moule; ceci permet d'obtenir une pièce très proche de son état final ce qui réduit le nombre d'interventions d'usinage et de finitions nécessaires à son aspect définitif; si vous ajoutez à cela le fait que les équipements nécessaires pour produire ces vilos de type "cast" sont relativement bon marché, il est facile de comprendre pourquoi ce type de vilebrequin est celui le plus répandu et choisi dans les usines de production produisant ce type de pièce !

Les distributeurs arrivent ainsi à proposer des pièces de plus en plus résistante en les affichant à un peu moins de $200 !

Pesant à peine 66 lbs, Ce vilebrequin très léger de marque Eagle's forgé 4340, pour big-block Chevys est donné pour supporter jusqu'à 1500 hp. Ils sont disponible pour des course de 4.000- et 4.250-inch, et peuvent proposer des “smaller 2.100-inch rod journals” pour ceux quie cherchent à diminuer les frictions !

à l'inverse, le processus de forge requière l'utilisation de presses très très puissantes et finalement bien plus d'opération d'usinage et de finition ! Forger la pièce en métal nécessite de chauffer un cylindre plein presque à l'état liquide, de le marteler et le presser ensuite avec ces puissantes presses, et de le laisser refroidir dans cet état ! C'est donc l'action de cette compression qui crée un produit dont le métal est plus résistant que celui du modèle "casting" !

Sur un modèle "moulé", la structure de grain ressemble au sable de plage," explique Tom Lieb de la célèbre marque "Scat". "Dans une modèle Forgé, la force de la Presse comprime ces grains ensemble et transforme l'état de surface en le rendant lisse; comme l'espace entre les molécules est compressé, chaque molécule est forcée de s'accrocher avec la molécule suivante." C'est ainsi que la comparaison entre un vilo "moulé" et un vilo "forgé" démontre l'inconvénient au niveau du prix de fabrication ! C'est essentiellement le coût des presses hydrauliques utilisées dans le processus de forge qui est extrêmement chère, ce qui entraine forcément un produit plus coûteux en bout de chaine de production ! Attendez-vous donc à ce que les prix commencent au minimum à $500 pour le moteur le plus populaire (genre le Chevrolet 350ci).

Considérez que les vilebrequins de type “Billet” sont comme une ramification des modèles forgés; en effet, tout comme les vilos forgés, les “billet” commencent sous la forme d'un large lingot cylindrique de métal. toutefois, alors que celui du vilo forgé est compressé durant le processus de forge à l'aide de puissantes presses, le lingot d'acier utilisé pour réaliser un vilo de type “billet” est quant à lui déjà forgé et ne nécessite donc pas les opérations réalisées avec ces presses !

La différence entre les 2 se situe au niveau de la méthode employée pour façonner ces lingots cylindriques de métal en vilebrequin..." La bar de métal utilisée pour créer un vilo forgé SBC de 4 inch (small block chevrolet) mesure 4.75-inches de diamètre, (environs 12 cms), et sa largeur total mesure 6.75 inches (environs 17 cms), une fois le processus de forgé complet" dit Lieb (spécialiste des vilebrequins aux usa); "la barre de métal utilisée pour un vilo 'billet' pour la même course (stroke de 4 inch) est plus large, parfois jusqu'à 8 inches, (Environs 20 cms), pesant 350 lbs en comparaison des 150 lbs pour un vilo forgé; au lieu de tordre et broyer le métal dans différentes directions, (comme c'est déjà le cas pour un vilo forgé), un vilebrequin “Billet” est réalisé par projection à distance ainsi le métal se dépose parallèlement sur la longueur entière du vilebrequin." à cause du matériel spécialisé mais aussi des laboratoires nécessaires à la réalisation des vilebrequin “billet', ces modèles sont les plus chers de tous; certain spécialiste pratiquent des prix pouvant aller jusqu'aux alentours de $3000...En fait comme il est clair qu'un vilo de type Billet est plus costaud qu'un vilo de type forgé et comme il n'y a pas d'équivalence dans l'industrie, les divers fabriquant will duke it out later in the story and we'll let you make the call.

Résistance (Strenght) :

Avant de délibérer sur la spécificité de la métallurgie, il y a des caractéristiques de résistance universelles et communes à tous les castings et forgings mais ne veut pas dire grand chose sans valeurs données.

Dans un laboratoire spécialisé, la résistance du métal à été testée en tirant sur une barre ronde d'un pouce de diamètre, (2,54 cm), jusqu'à ce qu'elle se casse; ce test de tension, (le “tensile strenght test), détermine la quantité de force nécessaire pour commencer à étirer la barrst”e; le “yield strength test” démontre quand à lui la force nécessaire pour continuer à étirer cette même barre; la différence entre le test de résistance “tensile” et “yield” entre les vilos moulés et les forgés est réellement perceptible; "Avec le modèle “moulé”, il suffit de réduire la section étirée (ainsi réduite en diamètre du à ce test de tension), de la barre de 6 % pour qu'elle se casse explique " Lieb”, alors que la section étirée par ce même test d'un vilo “forgé” peut être réduite jusqu'à 20 % avant de se rompre

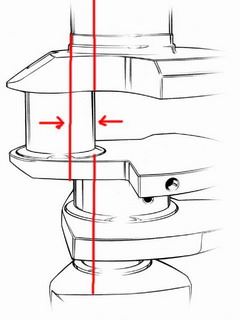

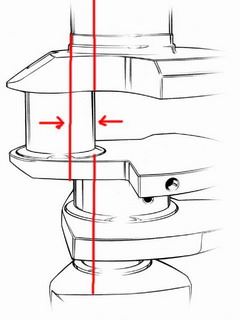

CUn tour de vilebrequin correspond tout simplement à la portion sur laquelle les bielles et les portés de vilo, (main journal) réalisent aussi chacune d'entre elles un tour complet. Stroker et dépasser les valeurs classique des vilebrequins déplace bien plus loin les portées des bielles, (rod journal), de celles du vilebrequin, (main journal), et par conséquent réduisent la valeur de l'overlap (tour complet compte tenue de son diamètre); Réduire les diamètres aussi bien des portées de bielles que celles du vilebrequin, diminue les frictions parasites mais compromet la résistance !

Metallurgy :

Comme un alliage est essentiellement constitué de fer, la petite quantité de métal ajouté à ce fer est ce qui détermine les différences de résistances de la matière utilisée se classant ainsi dans différents rangs d'aciers.

Un ensemble de standard à été établi par la société américaine des métaux (l' ASM) déterminant ainsi les différents rangs de métal, complétés de leur nomenclature; "pour une entrée de gamme de vilos moulés, en augmentant par exemple la quantité de carbone dans le fer, on améliore la résistance de la pièce," dit Alan Davis de la société “Eagle Specialty Products”.

La plupart des vilos standard, de base, qui sont réalisés en fonte, ont généralement une résistance de tension (souvenez vous plus haut le “tensile test”), d'environs 70,000 à 80,000 psi; en augmentant légèrement la proportion de carbone dans le fer, l'on produit le fer “nodular” (nodular iron cranck), permettant d'accroitre la résistance à la tension jusqu'à un résultat correct de 95,000 psi !

Tous ces matériaux sont amplement utilisés par les sociétés de fabrication, mais ne pourront cependant pas satisfaire les commercialisations plus sérieuse de vilo “stroker” et garantir leur résistance pour ces applications précise !

Couramment utilisé dans les entrées de gamme de production de vilebrequin, l'acier moulé, (le “cast steel”), contient une épatante proportion de carbone en comparaison du fer nodular, (nodular iron), et le fameux “tensile test” pousse le résultat jusqu'à 105,000 psi; "dans un moteur “small-block” typique, un vilo de type “cast-steel” peut facilement supporter un bon 500 hp, (nous les avons même vue encaisser des niveaux de puissances bien supérieur malgré tout nous recommandons tout de même l'utilisation d'un vilo “forgé”” pour des applications dépassant cette valeur déjà respectable de puissance réelle !)

Pour en revenir au thème principal, la fabrication de vilos forgés provient de l'utilisation d'alliages d'acier tels que le 1010, le 1045, et le 1053; alors que leurs test de résistance à la tension sont assez similaires à ceux des “vilo en acier moulé, (les cast steel cranks), leur taux d' élongation est plus de trois fois supérieur !

Cela démontre que ces matériaux sont beaucoup moins “cassant” et qu'ils résistent mieux avant de céder ! Et pas des moindres car leur durabilité finale dans le temps est bien plus importante face à celle des vilebrequins “steel cranck” disponibles sur le marché; les vilos forgés contiennent une proportion important de carbone, mais ils leur manque du chrome et du nickel lorsque ces dernier proviennent des alliage de base utilisés pour les vilos forgés “bon marché” , explique Scat's Lieb (Scat's est une marque reconnu de vilebrequin aux usa); "dans ces types d'alliages, le chrome et le nickel est justement ce qui les rend plus dur; il y a d'autre matériaux implantés (involved), cependant ils servent surtout à avoir l'assurance que l'ensemble va se mélanger correctement et qu'il n'y aura pas d'impact sur la solidité de l'alliage final.

Le rang de L'acier le plus couramment utilisé est le 5140, qui se vante de résister au test de tension jusqu'à la valeur d'environs 115,000 psi; ce matériaux avait la réputation et continuait jusqu'à présent d'être vu comme un excellent choix pour les budgets course serré, mais est depuis un peu plus d'un an moins répandu en raison de l'abordabilité grandissante des vilebrequins réalisés en acier de qualité prenium; cela inclu les aciers forgés de type 4130a et 4340, pour lesquels le test “tensile strength” leur fait atteindre respectivement les valeurs approximatives de 125,000 psi and 145,000 psi; les constructeurs de moteurs et les fabriquants de vilebrequins considèrent généralement ler 4340 comme l'acier idéale pour sa robustesse et sa durabilité. Et comme les distributeurs proposent à la vente ces vilebrequins 4340 à des prix débutant entre $500 et $600 pour la plupart des moteurs, ce niveau d'acier à grimpé en popularité, "nous avons plein de clients qui poussent jusqu'à 1,500 hp une vilo en acier forgé 4340," dit Eagle's Davis

The Ford FE maniacs at Survival Motorsports have just unveiled a forged 4340 crank in a 4.250-inch stroke for $1,150. For those on a tighter budget, Scat offers 3.980-, 4.125-, and 4.250-inch cast-steel cranks starting at $700. Survival has put over 750 hp through Scat cast cranks without any hiccups.

r r

have just unveiled a forged 4340 crank in a 4.250-inch stroke for $1,150. For those on a tighter budget, Scat offers 3.980-, 4.125-, and 4.250-inch cast-steel cranks starting at $700. Survival has put over 750 hp through Scat cast cranks without any hiccups.

Forge par torsion contre forge sans torsion(Twist via Non Twist Forging) :

Les vilebrequins forgés reçoivent systématiquement une opération de pressage dans des presses spécialisées, mais il y a 2 techniques différentes utilisées pour accomplir cela; La méthode la plus simple est de forger d'abord une des masselottes du vilo, (contrepoids), dans une presse plate, le vilebrequin étant ensuite soumis à torsion, et le cycle recommence avec la mise en presse de la masselotte suivante.

La 2èm technique appelée “Non twist foorging”, (forge sans torsion), consiste donc à forger simultanément , en une fois les 4 masselottes, (contrepoids), mais elle requière un matériel plus complexe.

En fait, la technique “Non-twist forgings” réduirait les contraintes interne du vilebrequin pendant le processus de fabrication , mais tout le monde ne se focalise pas la dessus pour autant !

"si toutes les variables sont contrôlées correctement pendant le processus de forge, il y aura réellement très peu de différence entres ces 2 techniques, (twist and non-twist forgings)," d'après James Humphries de Lunati industrie (célèbre marque de pièces perfos, entres autres les Arbres à Cames), "La plupart des vilebrequins sont de nos jours réalisés avec la technique “non-twist forged”, aussi cela n'a pas vraiment de sens d'argumenter sur ce point...c'est selon lui, plus l'occasion pour les revendeurs, de faire du marketing sur les publicité du produits” !

Traitement contre la chaleur :

En plus du matériau et de sa technique de moulage ou de forge, le traitement contre la chaleur peut considérablement améliorer la résistance d'un vilebrequin; le traitement par nitrate (Nitriding) est d'ailleurs la méthode prédominante utilisée pour le traitement contre la chaleur pour les vilebrequin d'entrée de gamme, ou l'azote ionisée est projetée et déposée sur la surface du vilebrequins pour être ensuite placé dans un four; en pénétrant de .010 à .012 inch idans la surface du métal, changeant ainsi la micro structure de l'acier, la dureté de cette surface est doublée et passe de 30 à 60 sur l'échelle de Rockwell, et la durée de vie est ainsi augmentée de 25 %.

Les fabricants ont généralement une préférence pour le renforcement par l'induction plutôt que le traitement à l'azote, qui résulte d'une pénétration profonde dans la surface du métal, (.050 to .060 inch); ce procédé utilise un puissant champ magnétique pour chauffer la surface. "il ya des inconditionnel et de conservateurs des 2 méthodes, cependant le traitement à l'azote et le plus répandu chez les distributeurs; le traitement par induction est plus localisé, alors que celui de l'azote traite le vilebrequin entier en une fois !Toutefois, comme précisé plus haut, la technique d'induction pénètre bien plus loin dans la surface du métal, ce qui permet which enables turning down the journals once or twice during rebuilds avant d'avoir à retraiter le vilo contre la chaleur !

Knife-Edging (découpe des bords):

Est-ce que le procédé “knife-edging” de découpe des contrepoids du vilo réduit réellement les frottements et fait iul augmenter la puissance ? Tout le monde ne le pense pas car ce procédé "Knife-edging” fut plus développé pour faciliter l'équilibrage que pour améliorer la puissance, et n'apportera finalement pas grand chose à un moteur “street", explique Callies' Dwayne Boes. "Like a snow plow, oil hits a knife edge and gets thrown all over the place when it should ideally land on the nose and flow off to the side. A bull-nose rounded leading edge is the most efficient, like the bow of a ship."

An area of the crank notorious for failure is where the rod journal meets the counterweight. Some contend that the forging process exacerbates this condition because it is the area where the grain flow is stretched and contorted.

Overlap :

Just as the term implies, journal overlap is simply how much of a crank's main and rod journal diameters overlap each other. As stroke is increased, moving the rod journals farther away from the main journals reduces overlap and compromises strength and durability. Likewise, smaller rod and main journals reduce bearing speed and friction, but also reduce overlap. "The reason why GM increased the size of the mains to 2.65 inches on a 400 SBC compared to 2.45 inches on a 350 was to maintain journal overlap with the longer 3.75-inch stroke," explains Judson Massingill of the School of Automotive Machinists.

Billet Or Forgeds quelle choix ?

Bien que nou ayons clairement souligné la hiérachie des différentes variété de moulage et de forge, nous n'avons pas spécialement déclaré lequel des deux procédé offrait la résistance ultime; très franchement, nous ne connaissons pas la réponse et nous n'essaierons pas de nous lancer dans la moindre suposition. Il y a là des arguments contraignant pour chacun des 2 choix provenant de sources aussi crédible les unes que les autres...ainsi nous vous laisson décider et vous faire votre propre opinion en vous aidant des informartions que nous exposons ici !.

Alan Davis d' Eagles (marque réputée de vilebrequin):

"Les gens pensent que les vilos de type “billet” sont plus costaud que les les forgés, mais ne n'est pas exact; “ les Billet” avaient obtenue cette réputation avant que les vilos forgés ne soient disponibles sur le marché et ils étaint donc à ce moment là, la seule solution proposée pour les la haute perdormance; avec un vilo de type forgé, le procédé de forge crée un grain de surface tissé (croisé/lissé). Alors qu'avec un vilo de type billet, ce grain en surface est juste disposé parallèlement au vilebrequin; le choix du “Billet” est conseillé si vous avez besoin d'un vilebrequin spécial sur mesure surtout depuis qu'il ne require plus, de nos jour, l'utilisation d'un équipemment couteux !

“Mais d'un autre côté, les presses de 200 tonnes nécessaires à la réalisation des vilos forgés coutent presque 6 fois moins chère et sont donc plus adatptée pour les grosses productions de pièces” !

Lorsque l'on regarde un vilebrequin cast (moulé), (situé à gauche), par rapport à un vilebrequin forgé, (situé à droite), il est évident que le procéssus de forge entraine un prix final plus élevé; effectivement, la surface rugueuse du vilo moulé montre que très peu de traitement et de finissions de surface sont nécessaires puisque le produit brut obtenu par moulage ressemble particulièrement au produit fini; l'apparence d'un vilo forgé présente quand à lui des reflets lisses, aussi il est évidément bien plus couteux à créer compte tenu des étapes nécessaires à réaliser après la prrocédure de forge au début de sa chaine de conception.

Tom Lieb de la marque “Scat” :

When looking at a cast (left) and forged (right) crank next to each other, it's obvious why the forging process fetches a higher price tag. The cast crank's rough surface shows very little finishing machine work is required, as the casting process yields a shape that closely resembles the end product. The forged crank's smoother appearance reflects more extensive machining operations required after it leaves the forging die.

"Un forgé n'est pas aussi costaud qu'un “Billet” car le processus de forge étire et découpe la structure du grain (au coeur de la matière même); la forge d'un vilebrequin commence sous la forme d'une barre de métal cylindrique, et elle subit ensuite des torsions pour créer les masselotes de bielles (contrepoids).

c”est ainsi que le métal qui était utilisé et présent à l'origine au milieu de la barre se retrouve maintenant vers l'extérieur, ce qui a pour effet d'étirer et de traumatiser la structure du métal, mais surtout de l'affaiblir ensuite, ce qui reveint à penser que certaines section de ceuili-ci serait à peine plus résistantes qu'une verion “Casting”, (Moulée), mais bien entendu c'est la résistance de l'ensemble qui prime... Avec le type “Billet”',il n'y a pas de risque de traumatiserr certaines zones car la structuure du graiin coure parrlèllement sur la longueur entière du vilebrequin.

Les “Forgés” sont plus résistant que les “Billet” au niveau des boulons et des axes car le metal ne subit pas d'étirement et est donc préservé; “ il n'y a plus un seul Top Fuel, Funny Car, Nextel Cup, ou écurie de F1 qui n'utilise pas un villebrequin de type “Forgé” donc vous devez maintenant un peu mieux comprendre pourquoi !"

Dwayne Boes de la société Callies :

"Si le matériaux de base utilisé est strictement le même pour les deux, un vilo “Forgé” est plus costaud qu'un modèle “Billet” car l' écoulement du grain est renversé et replacer billet because the grain flow is upset and relocated, néanmoins, il est plus facile d'obtenir un alliage spécial dans un matériaux de type “Billet” !

Judson Massingill de la société SAM :

"Au dessus de 600 à 700 hp, lees forgés sont tout aussi valable que les “Billet”, donnés avec un tour de porté adéquate, cependant, lorsque vous commencer par réduire cette portée dans sa circonférence avec les vilos de tyoe course longue (stroke), . However, when you start reducing the overlap with long strokes and small rod journals to reduce bearing speed, billet comes out on top. In our motors, billet lets us get away with less journal overlap."

Domestic versus overseas is a hot topic, but the increased competition has definitely resulted in lower pricing for consumers. While best known for its premium cranks, Lunati recently introduced its Sledgehammer line of entry-level 4340 cranks. They're 100-percent U.S. made, and this big-block Chevy unit retails for $860 from Summit.

Traditionally, the aftermarket has neglected the Buick, Olds, and Pontiac camps. When it comes to cranks, this still holds true, but to a lesser degree. The efforts of engine platform-specific diehards have yielded a specialty market of just-released steel cranks in some markets. In others, there are specialists for each engine family that can modify factory cranks to get you the extra displacement you crave. Of course, companies like Winberg, Bryant, and Moldex will make a custom crank out of billet for any engine, but we'll assume most hot rodders are working with a real-world budget.

It's been 30 years in the making, but Pontiac enthusiasts now have both aftermarket cast and forged cranks at their disposal. In the late '90s, Butler Performance teamed up with Eagle to produce the first aftermarket Pontiac crank, a cast-steel 4.250-inch unit for 3-inch main 326/350/389/400 blocks. Just this year, Butler Performance released 4340 forged cranks in 4.000-, 4.250-, and 4.500-inch strokes for 3-inch main blocks. The company also offers 4.000- and 4.250-inch 4340 cranks for 421/428/455 blocks with 3.25-inch mains. "Before we released these cranks, the only option was offset grinding a stock crank, which netted an extra 4 to 5 ci," David Butler says. "Forged cranks are so reasonably priced these days, there's no reason to even bother with a stock piece."

These days, it's no longer accurate to dub Mopars as "alternative makes." Companies such as Eagle and 440 Source have a full line of cast and forged cranks for Chrysler LA, B, and RB motors. Thanks to the big-block Chrysler's massive bore spacing, the modest 4.150-inch stroke of this forged Eagle crank nets 500 inches out of a factory 400 block.

Buick :

Unfortunately, the aftermarket hasn't stepped up with a new Buick crank design, but there are still options for increasing displacement by a good margin. According to Buick expert Mike Phillips of Automotive Machine, all 400, 430, and 455 Buicks have the same crankshaft. "Up to '74, the cranks have an 'N' cast into them, which some people think means nodular," he explains. "These things have massive 3.25-inch mains, so you can put 600 hp through them without a problem, and with a 3.900-inch stroke, Buick cranks have more overlap than many big-block Chevys." Thanks to that overlap, they can be offset ground up to 4.15 inches. "With a crank offset ground to 4.150 inches in a 455, you end up with 494 inches, but I think it weakens the crank considerably. It's better to offset grind the crank to 4 inches, in which case you can still externally balance the motor."

In the walk of big-block Oldsmobiles, there's the 425 and the 455. Noted Olds engine builder Dick Miller says that all 425 motors came equipped with forged steel cranks from the factory, while the number of 455s with steel cranks are less than 100. The 455 is the most common engine amongst Olds buffs, which features a 4.250-inch stroke. "Some 455 cranks had 'N' cast into them and others had 'CN' cast into them," Miller says. "The 'CN' crank is the stronger of the two." Although Eagle makes a replacement cast-steel crank rated at 700 hp, the factory piece is very stout. "The stock 455 crank can be offset ground to 4.500 inches, which equates to 496 ci. These cranks can handle up to 650 hp."

Never as mainstream as the Windsor or 385-series big-block, the Ford FE has been widely ignored by the aftermarket until now. Scat and Eagle both offer cast-steel cranks with strokes ranging from 3.980 to 4.250 inches. "The 390 is the most popular FE motor, and almost all of them had cast cranks," explains FE engine guru Barry Rabotnick of Survival Motorsports. "People used to get forged FE truck cranks and cut the nose down to fit into a car block or offset grind stock cranks, but there's no need to do that anymore. I've put over 750 hp through a cast Scat crank without any problems." Additionally, Survival Motorsports offers its own forged 4340 crank ina 4.250-inch stroke.

Taking advantage of the 385-series big-block Ford's towering deck height, Eagle and SCAT offer cast-steel cranks with strokes ranging from 3.850 inches to a jaw-dropping 4.850 inches. This rotating assembly is from SCAT

Taking advantage of the 385-series big-block Ford's towering deck height, Eagle and SCAT offer cast-steel cranks with strokes ranging from 3.850 inches to a jaw-dropping 4.850 inches. This rotating assembly is from SCAT

If All Else Fails :

If you need something done to a crank that no one else can peform [or if you need a nicely-prepped OE crank for a fun street driver-ed.] give Adney Brown of Performance Crankshaft a call. His specialty is repairing and modifying factory and aftermarket cranks to standards few others can touch. "For applications where aftermarket cranks aren't available, we track down old forgings and put whatever length stroke the customer desires," Adney explains. In addition to simple services, such as fixing up burned journals, Adney can lighten a crank, alter snout diameters, and weld up different flanges. "Don't consider it junk or give up your search until you call us first."

Since the American Society for Metals allows for some leeway within each grade of metal, the tensile strength ratings listed in this chart and elsewhere in the story are approximate, not exact figures. Nevertheless, they do adequately allow comparison among the strengths of different metal grades. While these represent just a small portion of all the steel alloys established by the ASM, they are the ones most common in automotive applications. Here's a quick rundown:

| MATERIAL: |

TENSILE STRENGTH: |

RATING: |

| Cast iron |

70,000-80,000 psi |

OE engines |

| Nodular iron |

95,000 psi |

OE engines |

| Cast steel |

105,000 psi |

strongest of the cast cranks |

| 1010/1045/1053 |

100,000-110,000 psi |

high-carbon factory-grade forging |

| 5140 steel |

115,000 psi |

sportsman-grade forging |

| 4130 steel |

120,000-125,000 psi |

premium alloy |

| 4340 steel |

140,000-145,000 psi |

strongest alloy for cranks and rods |

CHOISIR LES BONNES BIELLES

Tout savoir sur les bielles...et sur ce qu'il vous faut choisir ?

(By Steve Magnante...Photography by Steve Magnante)

(Traduction prévue dés que j'aurais un peu de temps...merci pour votre patience...Sauf si vous lisez l'anglais techniques sans soucis...tant mieux pour vous !) (Traduction prévue dés que j'aurais un peu de temps...merci pour votre patience...Sauf si vous lisez l'anglais techniques sans soucis...tant mieux pour vous !)

|

Cast Steel

|

Stock Forged Steel

|

Aftermarket Forged Steel

|

Fully Machined Forged Ste...

Fully Machined Forged Steel

|

True Billet Steel

|

Aluminum

|

Titanium

|

One of the most important decisions you’ll make when building your next engine is what rods to use. Whether it’s a slightly warmed-over stock rebuild or an all-out strip-stormer, any time you increase output, the first thing that’s tested is the strength of the connecting rods. Ignoring weight issues, most connecting rod upgrades do not add significantly to power output. What they do is far more important: They allow the ported heads, hotter cam, extra carburetion and other hop-up tactics to complete their mission. Let’s take a look at the battle zone tucked away in your crankcase.

As a piston reciprocates between top dead center (TDC) and bottom dead center (BDC), the rod it’s attached to experiences power loads and inertia loads. Power loads result from the expansion of burning gases during combustion that push down on the head of the piston and cause the crank to turn. Thus, power loads are always compressive in nature. This compressive force is equal to the area of the bore multiplied by the chamber pressure. A cylinder with a bore area of 10 square-inches (3.569-bore diameter) with 800 psi of pressure is subjected to a compressive load of 8,000 pounds. That’s 4 tons that the connecting rod must transmit from the piston to the crankpin, and do it hundreds of times per second at racing speeds.

Inertia loads are both compressive (crush) and tensile (stretch). To better understand them, let’s pull the heads off the engine and forget about the combustion process for a moment. When the rod is pulling the piston down the bore from TDC, the mass of the piston plus any friction caused by ring and skirt drag imparts a tensile load on the rod. Once the piston reaches BDC, the dynamics shift. Suddenly the rod is pushing the mass of the piston as well as the friction load back up the cylinder bore, and a compressive load on the rod results. Then the piston stops and reverses direction to head back down the bore, so the inertia of the piston, once again, tries to pull the rod apart as it changes direction. The size of the load is proportional to the rpm of the engine squared. So if crankshaft speed increases by a factor of three, the inertia load is nine times as great. At 7,000 rpm, a typical production V-8 with standard-weight (read “heavy”) reciprocating parts can generate inertia loads in excess of 2 tons, alternately trying to crash and stretch the poor rods.

OK, now we’ll reinstall the heads, turn the fuel pump and ignition system back on, and restore valve operation. The principles of inertia loading are the same, but conditions become even more severe now that the plugs are firing. Even more tensile loading on the rod comes from the work required to suck air and fuel through the intake tract and into the combustion chamber during the intake stroke. Once the piston reaches BDC, both valves close and the rod must push the piston back up to TDC on the compression stroke. But near the end of the trip toward TDC, the spark plug fires and the compressed fuel mixture begins to expand with opposing force before the piston reaches TDC. This causes a sudden surge of compressive energy that must be resisted until the orientation of the crankpin makes it mechanically possible for the piston and rod to change direction and be pushed back down to BDC during the power stroke. Remember, the size of the loads is proportional to the rpm of the engine squared. But that’s not all.

By far, the greatest test of a rod’s integrity is experienced near the end of the exhaust stroke when the cam is in its overlap phase. In overlap, both valves are open as the piston pushes the last remnants of spent combustion gas out the exhaust port. The intake valve is held open so that fresh intake charge is available the very instant the piston begins generating suction on the downward intake stroke. What makes the overlap period so hazardous is the fact that there is no opposing force applied to the head of the piston (in the form of compressed gas) to cushion the change in direction. This is the load that stretches the rod, ovals the big end, and yanks hardest on the fasteners. If you don’t want your engine to scatter, you’ve got to make sure the connecting rods are always one step ahead of any performance upgrades. But which ones are right for you? Read on for a complete rundown.

Cast-Steel

We won’t waste much time discussing cast-steel rods because they’re poorly suited to any type of serious performance use. Though the casting process is very inexpensive and results in “near net” shapes that require minimal machining, the lack of a cohesive grain pattern and compromised molecular binding yields brittle parts. Trust us, brittle connecting rods are the last thing you want in a performance engine.

In the ’60s and ’70s, American Motors, Cadillac, Buick, and Pontiac all used cast rods in a wide variety of engine designs. In an effort to improve molecular binding and strength, the molten metal was injected into the mold cavity under high pressure. The resulting castings may have been good enough for use in everything from GTOs to Jeeps, but they have no place in anything other than the most fanatical numbers-matching restoration effort. Worst of all, these cast parts had to be made heavier than comparable forged rods to maintain strength. When you consider that a cast “Arma-Steel” Pontiac 455 rod weighs 31.7 ounces and a stock Chevy 454 forged rod weighs 27.4 ounces, you’ll agree they’re the automotive equivalent of recycled cardboard.

Stock Forged Steel

Original-equipment forged steel rods are the next step up the strength and reliability ladder. Detroit-sourced OE-forged rods begin life as bars of carbon steel that are passed through a rolling die. The rolling process compacts the molecular structure and establishes a uniform, longitudinal grain flow. The bars are then heated to a plasticized state, inserted into a female die, and pressed into the near-final shape while a punch locates and knocks out the big end bore. In doing this, the grain flow at the big end is redirected in a circular pattern, like wood fibers surrounding a knot, and excellent compressive/tensile strength results. Finally the rod is put through a trimmer (that leaves the characteristic thick parting line on the beam), the big end is severed and machined to create the cap, bolt surfaces are spot-faced, then final machining and sizing take place.

But there are some drawbacks. When the forging hammer hits the hot bar, heat transfers from the bar to the hammer causing a phenomenon called de-carb (decarburization). Here, trace amounts of the carbon in the steel migrate to the surface resulting in a rough finish full of what metalurgists call “inclusions.” An inclusion is described as anything that interrupts the surface of the metal, or a lack of cleanliness (impurities) in the material. The effect of a surface inclusion can be likened to a nick in a coat hanger. Bend it enough times and the wire will fail, usually right at the nick. The rough surface caused by de-carb affects the surface to a depth of 0.005 to 0.030 inch and is packed with inclusions that are a breeding ground for cracks. The old hot rodder’s trick of grinding and polishing the beams is a valid solution to this problem, though far too labor-intensive to ever be considered by Detroit.

When it comes to inclusions caused by impurities, Detroit’s need to control costs can result in purchases of bulk steel that may (or may not) contain contaminants such as silicon that are not detected during manufacture. Such impurities can interrupt the grain boundaries between the parent molecules and lead to a fracture minutes or years after the rod is first installed in an engine. It’s a matter of luck and what kind of abuse the flawed rod is subjected to.

With very few exceptions, the weakest link in a stock forged rod is the fastener system. The rod bolt is usually the most marginal component. Simply upgrading from stock bolts to quality aftermarket replacements can improve durability by 50 percent. Just be sure to have the big end re-sized to restore concentricity any time the bolts are removed. Stock forged steel rods are an economical choice that should be able to handle one horsepower per cubic inch with quality fasteners, and as much as twice the factory-rated output if the beams are polished.

Aftermarket Forged Steel

Attention to detail and better parent material are the main attractions offered by aftermarket forged steel rods. Though the forging process is much the same, aftermarket rods are typically made from high- carbon SAE steel such as 4340, 4140, and 4330 that is far superior to the low-carbon 51-series steel used in most OE-forged rods. The SAE certification system quantifies the purity of the metal via microscopic examination that computes phosphorous and sulphur content, individual grain size, and other key indicators. By using SAE-certified material, makers (and users) of aftermarket forged rods can rest assured that hidden impurities are not lurking deep within the molecules to compromise strength.

Most aftermarket forged rods benefit from extra care during the critical machining operations. This alone can make or break a connecting rod… literally. The assumption that careful hands have assured closer tolerances and accuracy in the finished product is a valid one. Usually no heavier than stock rods, aftermarket forged rods already come equipped with premium fasteners and should be included in any street and strip engine assembly that will run in excess of 6,500 rpm with stock stroke or 5,500 rpm with increased stroke. The prices keep tumbling, and more applications are available now than ever. There’s no excuse not to step up.

True Billet Steel

True billet steel rods are fairly uncommon in today’s marketplace. Manufacturing begins when rough shapes are flame-cut from a plate of premium quality forged high-carbon steel (usually SAE 4340), then finish-machined to the required final specifications. Similar to cutting a pattern from a sheet of cloth, manufacturers benefit from true billet rods because they do away with the need to make expensive forging dies. These dies can cost between $35,000 and $45,000 a pair, and several may be needed to supply the wide range of shapes and sizes needed to fit all the various applications in the hot rodding galaxy. On the contrary, the dimensions and physical characteristics of a true billet rod are only limited by the size of the plate it will be cut from.

Although the rolling process that creates the plate of parent material gives a uniform, longitudinal grain flow with excellent molecular bonding properties for outstanding strength, there is one minor shortcoming. True billet rods lack the circular grain flow inherent to the big end of forged steel rods. Instead, the longitudinal grain flow continues undisturbed throughout the shoulder and cap sections. This does compromise some strength, but industry experts say it is a minor issue and is responsible for, at worst, a 15-percent reduction in the ultimate hoop strength of the bearing hole.

On the positive side, true billet rods are inherently free from the surface degradations caused by the forging process. A fully machined billet rod has virgin, high-quality material of uniform composition all the way from the core to the external surface. This makes it more resistant to the formation of cracks, a detail that more than makes up for the stubborn grain flow at the big end.

Fully Machined Forged Steel

Commonly misidentified as “billet” rods, fully machined forged steel rods are exactly what the name implies. Quite simply, they’re premium-grade forged rods that are treated to a high-tech shower and shave. The machining process eliminates undesirable surface imperfections and allows improvement of the shape for increased strength and/or reduced mass.

Before the advent of readily available CNC-machining equipment during the last 15 years, the material removal had to be performed on manual machines at great expense. Combined with the cost of the needed forging dies, the primary exclusive benefit of forged rods (dedicated big end grain flow) was not deemed to be worth the added expense, so most high-end manufacturers stuck with true billet rods. But with the manufacturing cost reduction made possible by automated CNC workstations, the economics shifted and it has become possible to couple the advantages of a forging with a pristine machined billet-like surface in the same rod. It truly is the best of both worlds, and for this reason, fully machined forged steel rods are the ultimate choice for strength where weight savings of the reciprocating assembly is not a primary goal. They’re a great choice for any high-performance application short of Top Fuel.

Aluminum

Aluminum rods are manufactured by the forging process, or they can be cut from a sheet of aluminum plate, billet-style. Aluminum rods are generally 25- percent lighter than steel rods, and for this reason they’re very popular with racers looking to shed mass from the reciprocating assembly. Lighter reciprocating parts demand less energy to set into motion, allowing more of the force of combustion to be applied to the wheels. Lower reciprocating mass also allows the engine to gain crank speed faster for quicker rpm rise after each upshift, to keep the engine near the peak of the power curve. That’s the good news.

The downside is that aluminum has a much shorter fatigue life than steel, perhaps one-tenth as long in a racing environment. This means you’ll have to measure for stretch and replace suspect rods at regular intervals to stay ahead of possible catastrophic failure. How long will they go? That depends on how hard they’re loaded and if they’re abused. We’ve all heard stories about hot rodders getting 100,000 street miles out of a set of aluminum rods. Could be. But the fact remains that aluminum has a tendency to work-harden with use. Going back to the analogy of the coat hanger, if you keep twisting it, it’ll break. That’s work hardening, and an aluminum coat hanger can’t handle the same strain for nearly as long as a hypothetical steel coat hanger.

Another hassle is the fact that aluminum rods must be made physically larger because the ultimate tensile strength is about half that of a good steel rod. The added bulk often causes clearance problems inside the crankcase, especially when they’re swinging from a stroker crank. Some aluminum rod users abuse them without even knowing it. A cold motor must be warmed thoroughly because the expansion rate of aluminum is twice that of steel. The difference in expansion between the steel crankpin and aluminum big end can restrict the oil film clearance until the temperature of all parts stabilizes. Wing the throttle on an ice-cold motor, and you might be looking at spun rod bearings, or worse.

Aluminum rods can handle plenty of horsepower. You’ll want to check with the manufacturer for specifics, but it is safe to say that 2 horsepower per cubic inch is just the beginning. We’ll err on the side of caution and say that aluminum rods are best suited to race-only engines where regular inspection can ward off potential trouble.

Titanium

Got a huge wad of cash burning a hole in your wallet? Then you’ll want to know that titanium rods offer the highest strength-to-mass ratio of them all. A well-designed titanium rod is about 20 percent lighter than a comparable steel rod. Titanium is the most abundant element in the earth’s crust, but it must be alloyed with other metals before it has the properties needed for the manufacture of connecting rods. The most common alloy is called “Titanium 6-4” because it has 6 percent aluminum and 4 percent vanadium to improve machineability.

Like steel and aluminum rods, titanium rods can be forged or cut from a billet. Given a choice, titanium rods are most durable when manufactured by the forging process. This is because the grain size of even the best aerospace grade titanium is less than steel. In a Richter-esque grain-sizing scale where a 6 rating is twice as tight as a 5 rating, titanium rates between 5 and 6 while high-carbon steel is far more cohesive, rating as high as a 9. To offset the possible negative impact on strength, a fully machined forged titanium rod is the best type thanks to the improved grain structure around the big end versus a cut-out true billet titanium rod.

Though raw titanium costs five times as much as raw carbon steel, the average retail cost of a set of titanium rods is “only” about twice that of steel. The increased consumer cost reflects the fact that titanium becomes “gummy” when machined and requires specialized tooling and slower feed rates. Titanium expands at about the same rate as steel and is resistant to work hardening, so you could run ’em in your street car with no problems as long as your wife never sees the credit card bill. So where do titanium rods really shine? In any all-out racing effort where an approximate 15-percent reduction in ultimate tensile strength is an acceptable trade-off for an approximate 20-percent reduction in connecting rod weight. As for ultimate power capacity, know that they’re used in everything from 9,000-rpm NASCAR motors to a handful of 6,000hp Top Fuel motors (though most teams use aluminum). With the right communication between you and the manufacturer, they’ll handle anything you can throw at ’em. Just be sure not to scratch them! Titanium is very “notch sensitive.” Small surface imperfections caused by rough handling must be polished immediately, or they can grow quickly.

Date de création : 30/12/2009 @ 05:02

Dernière modification : 14/06/2010 @ 04:50

Catégorie : Technique automobile

Page lue 36758 fois

Imprimer l'article Imprimer l'article

| |

(Traduction prévue dés que j'aurais un peu de temps...merci pour votre patience...Sauf si vous lisez l'anglais techniques sans soucis...tant mieux pour vous !)

(Traduction prévue dés que j'aurais un peu de temps...merci pour votre patience...Sauf si vous lisez l'anglais techniques sans soucis...tant mieux pour vous !)

Achat Coup de Coeur

Achat Coup de Coeur

r

r

Haut

Haut